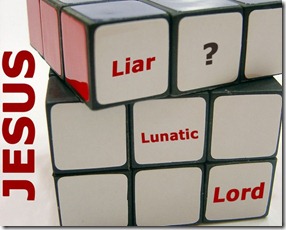

[Jacques] Maritain has hinted at the only way in which Christianity (as opposed to schismatics blasphemously claiming to represent it) can influence politics. Nonconformity has influenced modern English history not because there was a Nonconformist Party but because there was a Nonconformist conscience which all parties had to take into account. An interdenominational Christian Voters’ Society might draw up a list of assurances about ends and means which every member was expected to exact from any political party as the price of his support. Such a society might claim to represent Christendom far more truly than any ‘Christian Front’; and for that reason I should be prepared, in principle, for membership and obedience to be obligatory on Christians. ‘So all it comes down to is pestering MPs with letters?’ Yes: just that. I think such pestering combines the dove and the serpent. I think it means a world where parties have to take care not to alienate Christians, instead of a world where Christians have to be ‘loyal’ to infidel parties. Finally, I think a minority can influence politics only by ‘pestering’ or by becoming a ‘party’ in the new continental sense (that is, a secret society of murderers and blackmailers) which is impossible to Christians. But I had forgotten. There is a third way — by becoming a majority. He who converts his neighbour has performed the most practical Christian-political act of all.

Such a society might claim to represent Christendom far more truly than any ‘Christian Front’; and for that reason I should be prepared, in principle, for membership and obedience to be obligatory on Christians. ‘So all it comes down to is pestering MPs with letters?’ Yes: just that. I think such pestering combines the dove and the serpent. I think it means a world where parties have to take care not to alienate Christians, instead of a world where Christians have to be ‘loyal’ to infidel parties. Finally, I think a minority can influence politics only by ‘pestering’ or by becoming a ‘party’ in the new continental sense (that is, a secret society of murderers and blackmailers) which is impossible to Christians. But I had forgotten. There is a third way — by becoming a majority. He who converts his neighbour has performed the most practical Christian-political act of all.

*MPs – Members of Parliament in the UK and Canada, in the US write to your Congressman or Senator.

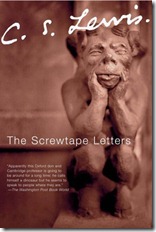

“Christians and politics,” Part 3 of 3 from C.S. Lewis, “Meditation on the Third Commandment,” God in the Dock (Eerdmans: 1970) 199.