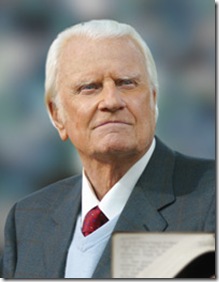

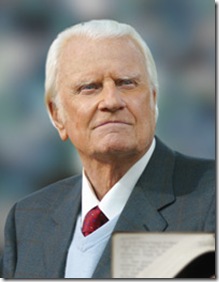

To better understand today’s reading from CS Lewis, I want to set it in the context that Jack himself had in mind. What do Christians believe about heaven? What does the Bible teach? Let me share the typical answer much of the church would give today (Can we let Billy Graham be the spokesperson?) followed by Lewis’s response to such thinking.

Q: Do you believe that we'll be reunited with our loved ones when we get to heaven? I deeply hope we will be, but with all the millions and millions of people up there, how will we ever find them? Maybe I shouldn't worry about this but I do. - Mrs. R.E.

A: Yes, I firmly believe we will be reunited with those who have died in Christ and entered heaven before us. I often recall King David's words after the death of his infant son: "I will go to him, but he will not return to me" (2 Samuel 12:23). This truth has become even more precious to me since the death of my dear wife, Ruth, a year and a half ago.

A: Yes, I firmly believe we will be reunited with those who have died in Christ and entered heaven before us. I often recall King David's words after the death of his infant son: "I will go to him, but he will not return to me" (2 Samuel 12:23). This truth has become even more precious to me since the death of my dear wife, Ruth, a year and a half ago.

And, yes, there will be a vast number of people in heaven, for every person through the ages who has trusted Christ for their salvation will be there. The Bible says that because of Christ's death for us, heaven will be filled with "a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb (Christ)" (Revelation 7:9).

But you shouldn't worry about getting lost, or never finding your loved ones in heaven - not at all. If God brought you together on this earth - out of all the billions of people who live here now - will He be able to bring you together in heaven? Of course.

Never forget: Heaven is a place of supreme joy - and one of its joys will be our reunion with our loved ones. But heaven's greatest joy will be our reunion with Christ, our Savior and Lord. Is your hope and trust in Him?

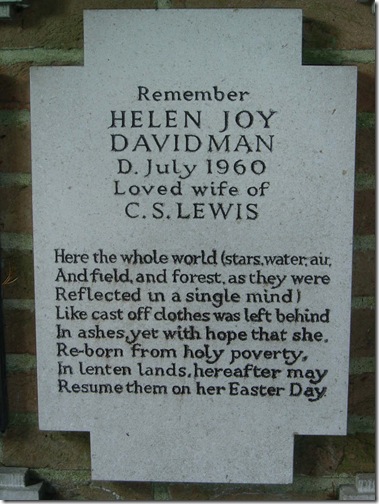

Lewis: You tell me ‘she goes on’. But my heart and body are crying out, come back, come back… But I know this is impossible. I know that the thing I want is exactly the thing I can never get. The old life, the jokes, the drinks, the arguments, the lovemaking, the tiny, heartbreaking commonplace. On any view whatever, to say ‘[Helen Joy] is dead’, is to say ‘All that is gone’. It is a part of the past. And the past is the past and that is what time means, and time itself is one more name for death, and Heaven itself is a state where ‘the former things have passed away’.

Lewis: You tell me ‘she goes on’. But my heart and body are crying out, come back, come back… But I know this is impossible. I know that the thing I want is exactly the thing I can never get. The old life, the jokes, the drinks, the arguments, the lovemaking, the tiny, heartbreaking commonplace. On any view whatever, to say ‘[Helen Joy] is dead’, is to say ‘All that is gone’. It is a part of the past. And the past is the past and that is what time means, and time itself is one more name for death, and Heaven itself is a state where ‘the former things have passed away’.

Talk to me about the truth of religion and I’ll listen gladly. Talk to me about the duty of religion and I’ll listen submissively. But don’t come talking to me about the consolations of religion or I shall suspect that you don’t understand.

Unless, of course, you can literally believe all that stuff about family reunions ‘on the further shore’, pictured in entirely earthly terms. But that is all unscriptural, all out of bad hymns and lithographs. There’s not a word of it in the Bible. And it rings false. We know it couldn’t be like that. Reality never repeats. The exact same thing is never taken away and given back. How well the Spiritualists bait their hook! ‘Things on this side are not so different after all.’ There are cigars in Heaven. For that is what we should all like. The happy past restored.

And that, just that, is what I cry out for, with mad, midnight endearments and entreaties spoken into the empty air.

C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed (London: Faber and Faber, 1961), 22-23.

Turned to God, my mind no longer meets that locked door; turned to [Helen Joy], it no longer meets that vacuum—nor all that fuss about my mental image of her. My jottings show something of the process, but not so much as I’d hoped. Perhaps both changes were really not observable. There was no sudden, striking, and emotional transition. Like the warming of a room or the coming of daylight. When you first notice them they have already been going on for some time.

Turned to God, my mind no longer meets that locked door; turned to [Helen Joy], it no longer meets that vacuum—nor all that fuss about my mental image of her. My jottings show something of the process, but not so much as I’d hoped. Perhaps both changes were really not observable. There was no sudden, striking, and emotional transition. Like the warming of a room or the coming of daylight. When you first notice them they have already been going on for some time.