When we come to man, the highest of the animals, we get the completest resemblance to God which we know of. (There may be creatures in other worlds who are more like God than man is, but we do not know about them.) Man not only lives, but loves and reasons: biological life reaches its highest known level in him.

But what man, in his natural condition, has not got, is Spiritual life—the higher and different sort of life that exists in God. We use the same word life for both: but if you thought that both must therefore be the same sort of thing, that would be like thinking that the ‘greatness’ of space and the ‘greatness’ of God were the same sort of greatness. In reality, the difference between Biological life and Spiritual life is so

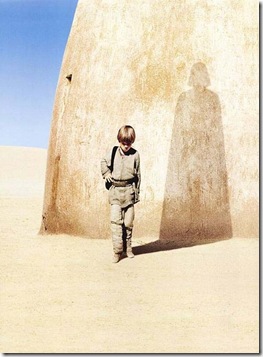

And that is precisely what Christianity is about. This world is a great sculptor’s shop. We are the statues and there is a rumour going round the shop that some of us are some day going to come to life.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (1952; Harper Collins: 2001) 158-159.